The James Watt Project

|

2019 marks 200 years since James Watt's death and bicentenary celebrations have been in the making for a while now. Born in Greenock in 1736, James Watt was one of Scotland's most famous inventors and, undeniably, one that played vital role in the dawn of the Industrial Revolution.

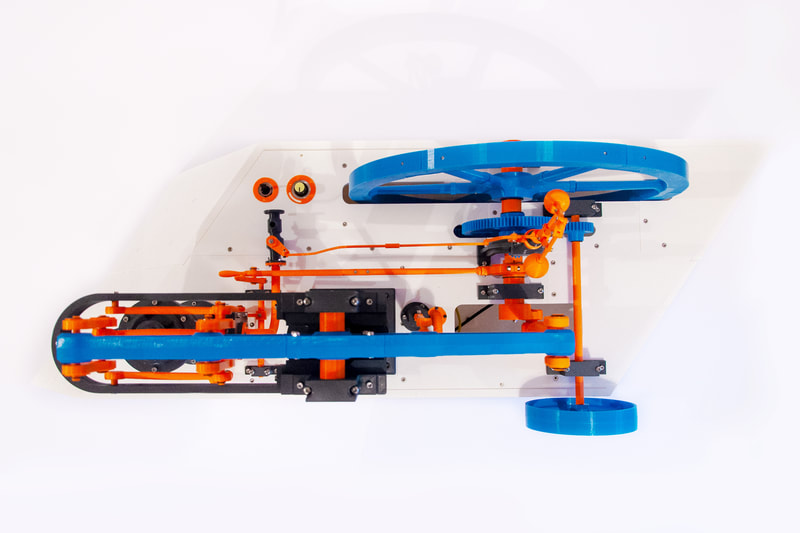

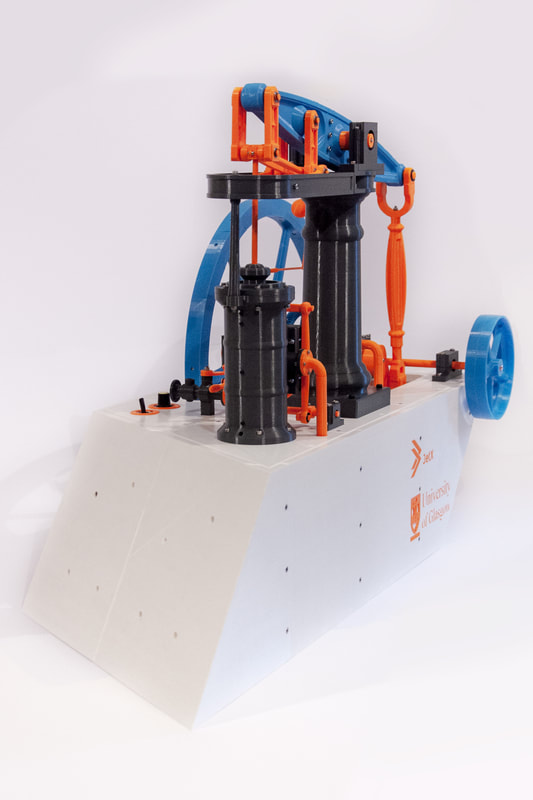

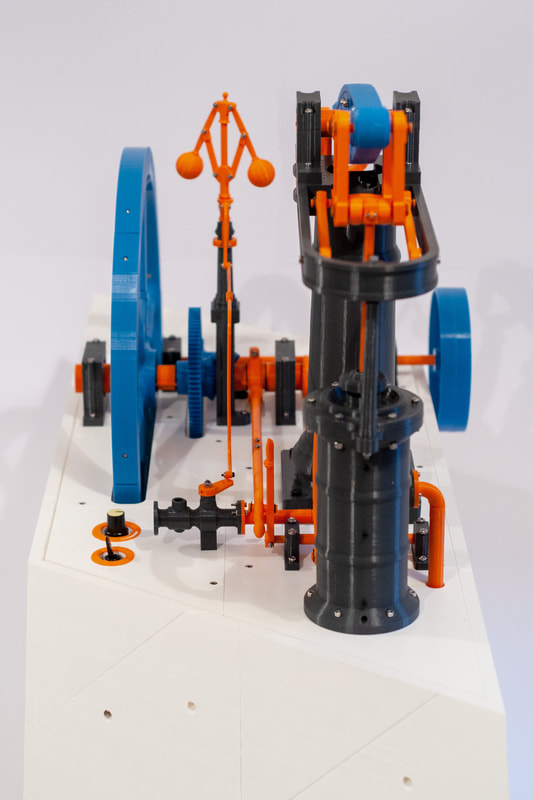

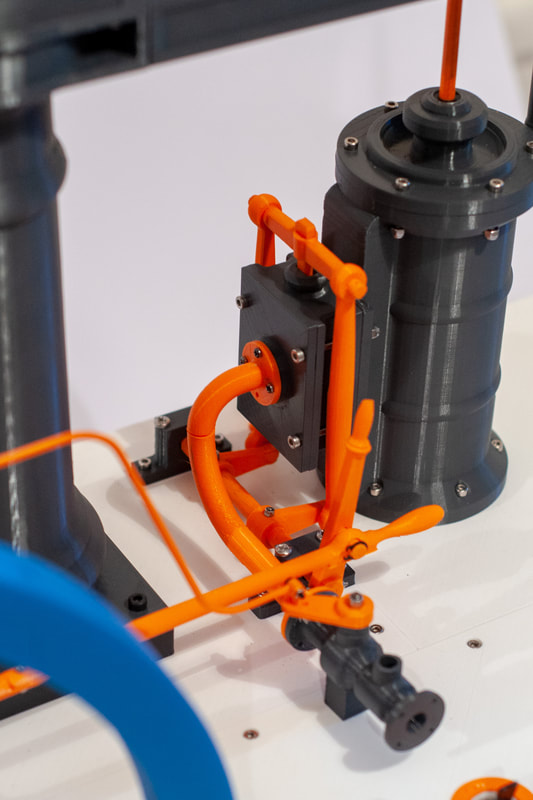

The University of Glasgow has planned multiple events to celebrate the legacy of James Watt and the idea of a working 3D-printed engine model was put on the table. We were honoured to be the first student organisation to be approached with this opportunity in December 2018, as the organisers recognised that thanks to our experience building jet engine models, we would be most capable of delivering this in time for a public exhibition which is now open. Prototyping began on the 16th of March 2019 and was completed 65 days later, transforming a total of 218 parts from CAD to reality for main components and development parts. |

- 800+ Total parts

- 324 Fasteners - 150+ 3D-printed parts - 29 bearings |

The James Watt Project was funded by

with the support of

DESIGN

The room for original design was always going to be very limited with a project like this, but that was fine with us. We wanted to focus on the building stage, the model's actuation and the delivery of an interactive exhibit, which kept us busy enough for just over 5 months.

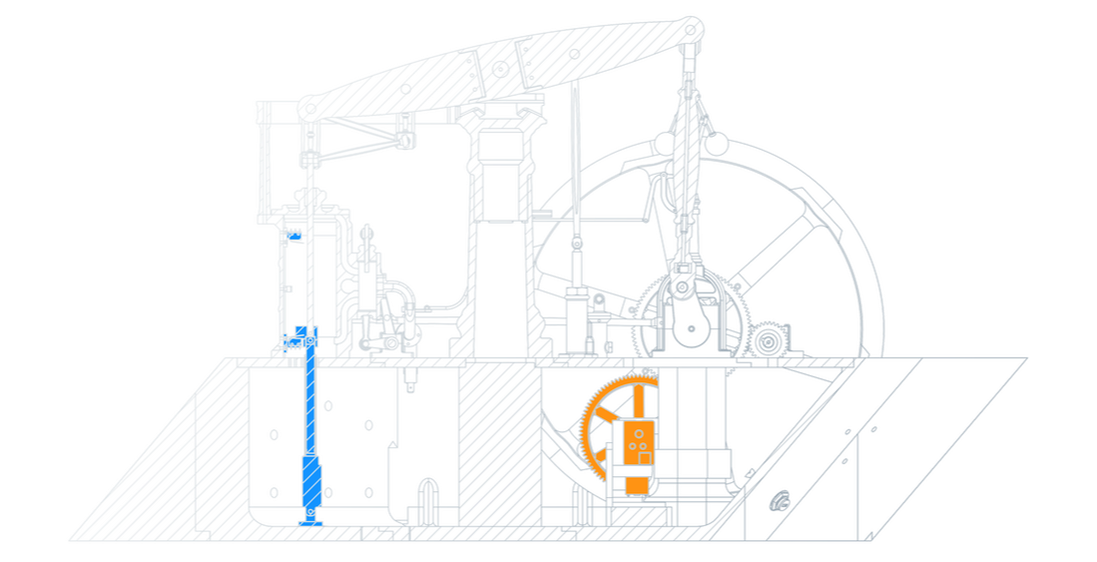

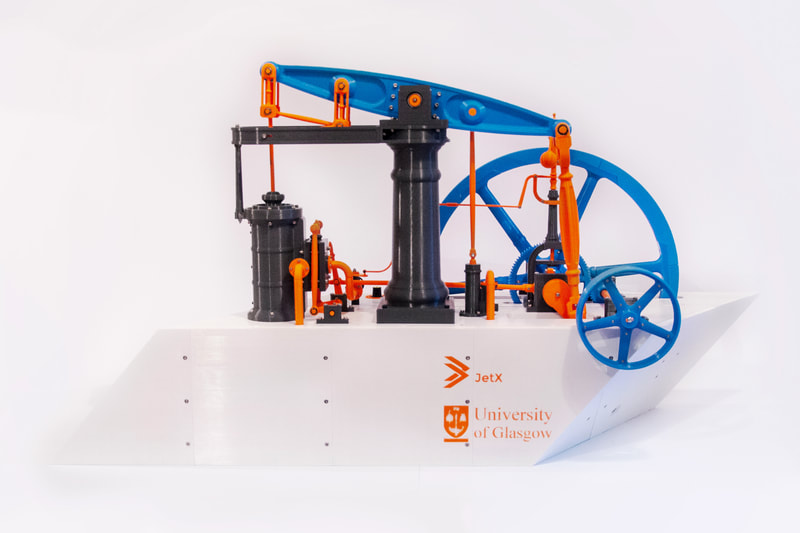

The design builds upon the earlier adaptation of Oliver Smith’s drawing for a model-sized beam engine by John Fall. John's fantastic work was an excellent starting point for us, that was followed by scaling adjustments, certain geometrical simplifications and a lot of time spent splitting and re-assembling parts for ease of 3D printing and assembly. A new, simple but modern base was designed to house the electronics and the components that move partially beneath the baseplate. The result is the largest additively manufactured working model of this design which features over 150 3D-printed parts.

The design builds upon the earlier adaptation of Oliver Smith’s drawing for a model-sized beam engine by John Fall. John's fantastic work was an excellent starting point for us, that was followed by scaling adjustments, certain geometrical simplifications and a lot of time spent splitting and re-assembling parts for ease of 3D printing and assembly. A new, simple but modern base was designed to house the electronics and the components that move partially beneath the baseplate. The result is the largest additively manufactured working model of this design which features over 150 3D-printed parts.

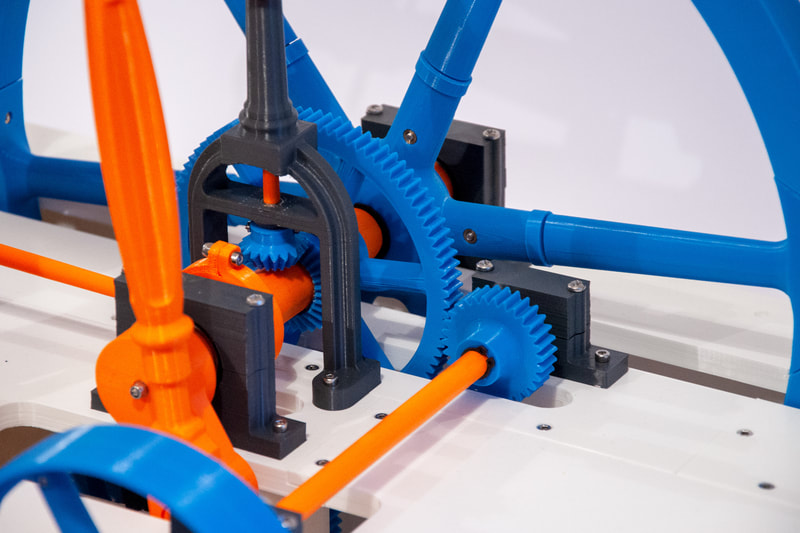

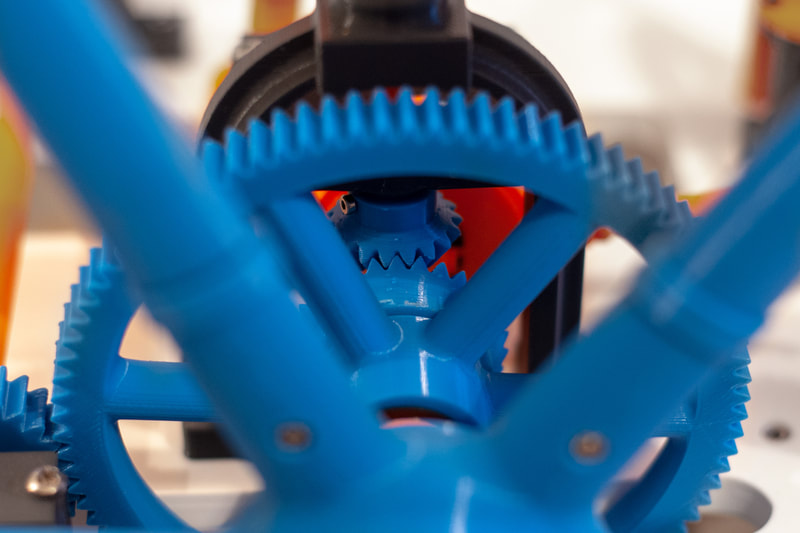

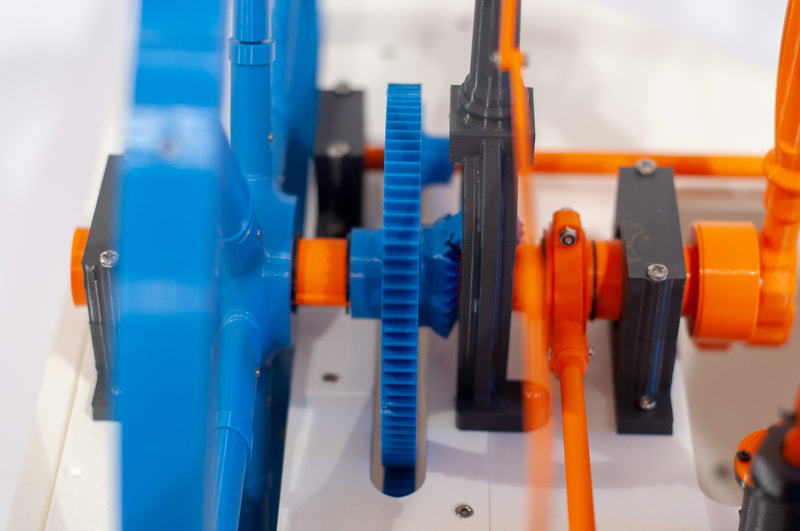

Our intention was to use a linear actuator to drive the model as close to the original piston action as possible. However, upon testing that, the specific actuator we had proved unable to deliver the motion wave that was needed for smooth operation (faster stroke in the centre and better acceleration/deceleration at the minimum and maximum positions). Instead, a third spur gear is housed in the base and is used to drive the model in order to demonstrate how the mechanical parts of the engine interacted, without the use of steam. This iconic engine of the industrial revolution has been recreated using one of the fastest developing technologies of the 21st century.

ELECTRONICS

An exhibition-ready setup

Electronics integration is one of our favourite parts of the building process and, just like in previous projects, the electronics system went through multiple iterations before taking its current form. The final circuit was much simpler than the ones featured on the X-Plorer engines and consists of:

- 1 DC motor with a reduction gearbox

- 1 capacitive touch sensor

- 1 tinyAVR Microcontroller

Both the principle of operation and the hardware assembly are fairly simple, but we were excited to be using a touch sensor that added an element of interactivity. Taking into account the length of the exhibition, we felt it would unnecessary to run the model continuously over prolonged periods of time, something that could also accelerate wear on certain components.

To overcome this, the system does not only respond to the touch sensor for switching purposes, but also executes a pre-programmed routine that smoothly ramps up, runs at nominal speed for around 35 seconds and finally smoothly ramps down, automatically bringing it to a stop.

To overcome this, the system does not only respond to the touch sensor for switching purposes, but also executes a pre-programmed routine that smoothly ramps up, runs at nominal speed for around 35 seconds and finally smoothly ramps down, automatically bringing it to a stop.

3D PRINTING

3D printing has always been our main manufacturing method due to its value for a very low number of parts, but a relatively high number of unique components; this project was yet another example of its suitability. The James Watt Engine Model was printed exclusively using Formfutura EasyFil PLA.

This time, the shortest print lasted for just 5 minutes, prototyping two of the embedded letters for the base. Even though the base is hardly eye-catching, one corner block was the longest part to be printed for this build, spanning over 56 hours 35 minutes, consuming 166m of white PLA in one go. Weighing just under 500g, the part was built using 22 processes, mostly varying the infill to values as low as 4% to save plastic despite the considerable volume taken up.

Among the parts printed, the shaft for the belt pulley wheel became the longest single part we've prototyped so far, measuring 27.7cm.

This time, the shortest print lasted for just 5 minutes, prototyping two of the embedded letters for the base. Even though the base is hardly eye-catching, one corner block was the longest part to be printed for this build, spanning over 56 hours 35 minutes, consuming 166m of white PLA in one go. Weighing just under 500g, the part was built using 22 processes, mostly varying the infill to values as low as 4% to save plastic despite the considerable volume taken up.

Among the parts printed, the shaft for the belt pulley wheel became the longest single part we've prototyped so far, measuring 27.7cm.

Printers Used

Stats

Development, testing & production of the James Watt Engine

|

3D-printed parts |

hours of printing |

meters of plastic used |

Gallery

Where is it now?

James Watt South Building Foyer

The model is now in its permanent (for the foreseeable future) home within the James Watt South Building. It can be visited Monday to Thursday, 09:00-17:00 and on Fridays 09:00-15:30.

Between June 2019 and September 2021, the model was on display in the University of Glasgow library as part of the James Watt and Glasgow Exhibition.

The model is now in its permanent (for the foreseeable future) home within the James Watt South Building. It can be visited Monday to Thursday, 09:00-17:00 and on Fridays 09:00-15:30.

Between June 2019 and September 2021, the model was on display in the University of Glasgow library as part of the James Watt and Glasgow Exhibition.

You can also find a full listing of bicentenary events, by visiting jameswatt.scot or by clicking on the icon below.